The Wondrous World of Wonderwall Studios

I’m no expert on the Netherlands—in fact, my cultural reference points for the region are limited to familiarity with breath-work guru Wim Hof, the Gold Member character from the Austin Powers films, and the endlessly inventive output of Amsterdam-based design firm Moooi. But getting to know Wonderwall Studios founder Jan Swinkels has left me with the impression of having encountered something quintessentially Dutch.

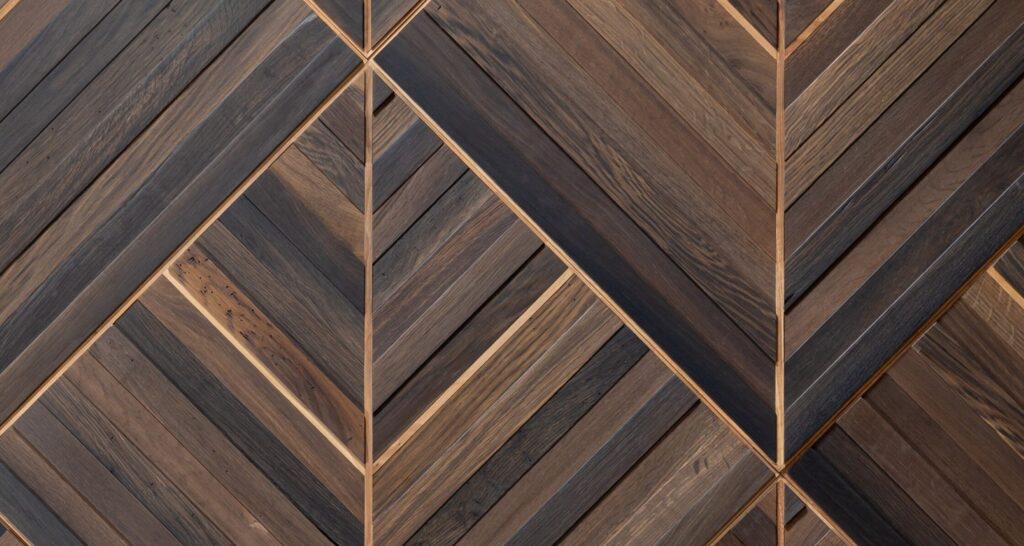

Detail of wall panel from the Phoenix collection (salvaged Teak) at the Hotel Breukelen in the Netherlands.

This characterization of “Dutchness,” is meant in the most complimentary sense, as both he and his company project a warm and welcoming aura, a genial enthusiasm, a mastery of the material at hand, and a global ethos that’s open wide to all manner of opportunity—a fair argument can be made that it’s this last quality that opened the door wide to Wonderwall Studios.

Jan Swinkels and wife Aanyoung Yeh with partners at the Indonesia atelier, exploring opportunities for the Mixed Salvage collection.

As Jan tells it, sometime around 2010 he encountered the proverbial fork, departing from the finance trajectory he had been following to “do something more entrepreneurial and adventurous.” The move first manifested in Doing Goods, a kind-of treasure-hunting concern focused on vintage cabinetry, decorative home accessories, clothing, and sustainably produced furniture, which he and wife Aanyoung Yeh discovered all across Asia. On one of these reconnaissance missions they observed the wonderful qualities of the hardwoods of some abandoned homes they’d encountered, ostensibly going to ruin in the Java humidity and heat: “It was all this amazing salvaged wood: beams, poles, skirting, floors from sheds… really diamond-in-the-rough type stuff.”

Wonderwall Studios Decorative wall panel from the “Parker” collection, Mixed Salvage line.

The rub, of course, was the formidable transport and climate costs of getting the wood back to the studio. The ingenious proposition—which is really the core innovation of Wonderwall—was the idea of bringing the studio to the wood, in a sense, rather than the other way around.

From derelict Javanese building to London’s Honi Poke restaurant. Quite a journey for this beautifully brindled reclaimed wood.

After connecting with a group of artisans in Java who were in close proximity to the raw material, the light bulb went off and Wonderwall was born. The idea, in essence, was to find stores of wood that would otherwise be consumed by the elements, or discarded outright, and create the product at the source, rather than incurring the huge inefficiencies of moving around great quantities of raw material.

The exceptional durability of Indonesian hardwoods has enabled them to withstand decades of exposure to the elements. It would be a shame for it to go to waste, but perhaps even more tragic to transport all of it.

The concept manifests today in Wonderwall’s wonderfully varied collections—each distinguished by the character of the wood and the character of each region—a consortium of fantastic places that presently includes Indonesia (mixed salvage and Teak), India (mixed salvage and a limited edition Pine collection); Vietnam (American Walnut); Italy (Olive wood); and the Ukraine (Bog Oak and Walnut).

Detail of a panel from the “Harvest” collection: the beguiling beauty of Bog Oak.

Each of the above locations offers a fascinating mythos that’s part and parcel of the uniqueness of the wood, but the story of Bog Oak is perhaps the most compelling. Just like it sounds, wood from this collection is oak found in the murky and mysterious depths of Central European bogs. The great trees have either fallen into the bogs, or been gradually inundated via natural expansion of the basin, and thus immersed in the anaerobic environment of compacted peat. The result is twofold: preservation and mineralization.

No small feat to get it out of the peat. Bog Oak extraction with help from a crane, a drone, and no little effort from an intrepid scuba diver named Ivan.

As one might imagine, Bog Oak presents a formidable array of challenges. “It’s only accessible during the warm season,” says Swinkels. “You have to get a local permit along with a crane and small truck, extract it and dry it, and do all that with care for nature…” He adds that it’s especially difficult these days because electricity is rationed. But if aesthetics count for anything, then Bog Oak is definitely worth the effort. The eons-long exposure to water results in minerals and iron binding with tannins in the wood, a natural staining process that proffers an enviable spectrum of coloration: from wheat-brown to tawny, rich amber, chocolate, and black-as-night. It’s no wonder that Bog Oak is historically prized, serving as the material of choice for the throne of none other than Peter the Great.

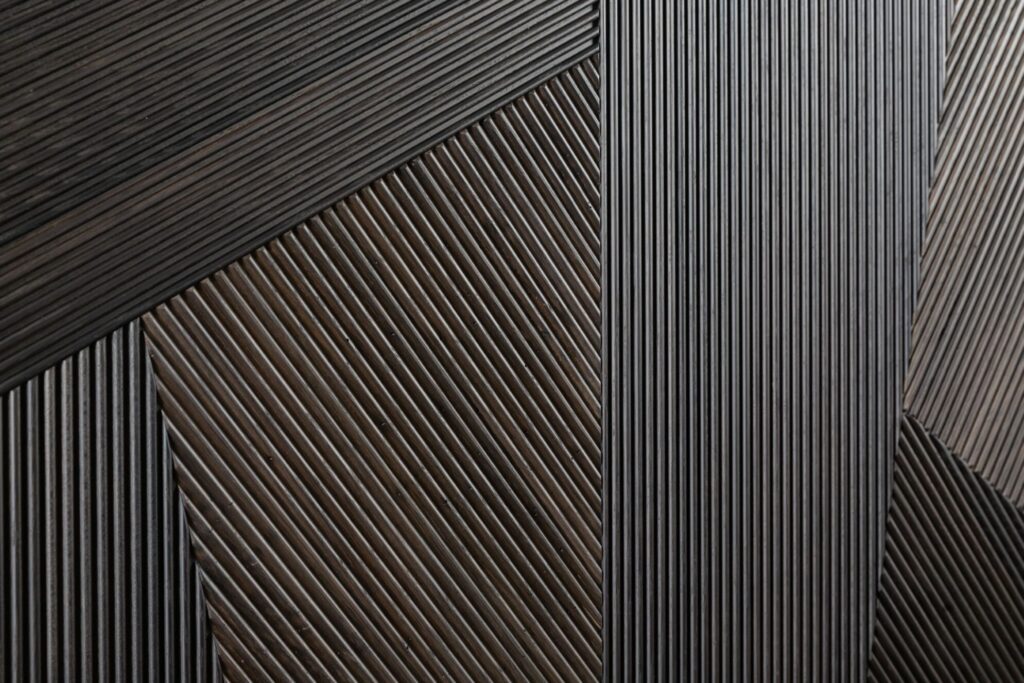

The Bog Oak Ridge collection offers a hypnotic, perspective-befuddling aspect worthy of M.C. Escher, jibing nicely with the species’ aqueous mysteries.

Swinkels aims to be as ecologically conscious as he can, even though this stance occasionally bumps up against the exigencies of running a financially viable business. The Olive wood collection uses pruned members or felled trees from olive groves—pruning and felling being routine protocol to maintain the viability of the orchard—and, again, wood that would typically be discarded (and consume fossil fuels in the very act of disposal).

Waves Collection. Olive Wood from Wonderwall Studios.

The only slight wrinkle in the model is American Walnut sourced from Vietnam, where it’s been imported from the U.S. Swinkels uses off-cuts and outer-ring sections from Vietnamese furniture manufacturers. So even though the raw material has been imported, he’s still using salvaged wood that would otherwise enter the waste stream. This also corresponds nicely with the intended aesthetic, as the parts deemed “unusable” by the manufacturers have a “beautiful, bright, almost pinkish hue.”

American Walnut as shown in the Crest collection. And below wrapping the pillars in the lounge at the Vandervalk Hotel in Breda, NL.

As far as the Walnut “wrinkle,” one of Swinkels’ most ambitious projects is securing a source for the wood stateside, which would mark the first Wonderwall partner located in North America. He’s been exploring some contacts in California (which makes for a nice correspondence with the California state flag tacked onto the wall behind him during our talk), but cautions that this can be a slow process: “I would love to set up something on the other side of the water. It fits our story and I’m almost there but it takes time… Maybe two years down the line. I visited the Amish near Chicago as a potential source, but this would be very difficult because they have no telephone, no email.”

The Notes collection (above) hints at the great variety of styles: from intricate carvings to straight-forward vertical and horizontal designs, geometric to curvilnear, overtly textural to subtler signs evocative of ancient hieroglyphs.

Totem (above) looks as if it could have been discovered on cave walls. Miles (below) has an Art Deco motif that evokes Mayan iconography.

Apropos of the challenges involved in the Wonderwall model language barriers for one—Swinkels remarks that finding good partners in these international locations is one of the most satisfying aspects of what he does: “When it works it’s absolutely wonderful, but it’s like a marriage… You both have to be headed in the same direction, at the same sort of phase in life. You need to be able to look each other in the eye and say are we going to do this: yes or no?” Thankfully, the answer has been “yes” enough times to give the world a fairly broad collection: two continents (with any luck soon to be three), six species (along with mixed salvage), and 42 unique collections.

The Phoenix Collection, in process.

Wonderwall Studios’ wood panels are appropriate for a wide range of venues. They’re mostly used in hospitality applications like lobbies, wellness centers, lounges, and cigar rooms, but also increasingly found in workplaces, “especially big tech, where clients often like to have a comfy, cool, accessible vibe.” Retail and residential are both gaining in popularity also. Among the many incarnations we find feature walls, counters/bar fronts, ceilings, bed headboards, cabinetry, tabletops, and acoustical ceilings/walls. All panels are solid wood, ranging in thickness from three to 40 millimeters.

The range of applications on display: from a Starbucks in Bucharest, to a spa in France, to a wall of guitars in Hilversum, NL that simply hums.

See the website to read more about Wonderwall Studios. And contact Founder Jan Swinkels at info@wonderwallstudios.com.

Leave a Reply