Live at Design Miami: Gonçalo Mabunda’s Weapons Chairs

Right on the heels of the Campana duo’s re-creation of childhood fantasy, Design Miami gives us Gonçalo Mabunda’s re-creation of a fifteen-year-long nightmare of civil strife. Born in 1975 in Maputo, Mozambique, Mabunda’s childhood was marked by the horrific backdrop of armed conflict.

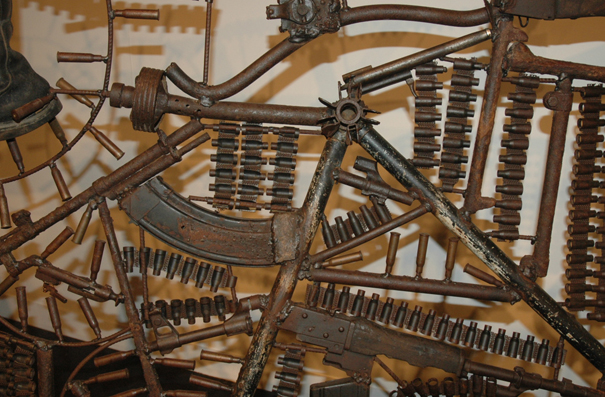

Weapons Chair. Designed by Gonçalo Mabunda. Exhibited via Perimeter Editions. Modeled with Julie MacKay.

Mozambique’s civil war was particularly protracted and gruesome: “over 900,000 died in fighting and from starvation, five million civilians were displaced … and many were made amputees by landmines.” The armament as remnant is a potent symbol of wars’ lasting influence on successive generations, since they remind us-as the inhabitants of war-ravaged nations are reminded daily-that war’s legacy is not easily effaced. In Mabunda’s nation, the plenitude of stockpiled weapons (many of which are still unaccounted for) is a habitual specter and a present danger, both evoking the recent horror and reminding us how difficult it is to dismantle the artifacts of conflict.

But Mabunda is trying his darnedest to do just that. Taking his cue from the “Throne of Weapons” initiative, which encourages the citizenry to turn in weaponry in exchange for productive tools such as sewing machines or bicycles, Mabunda has been beating the proverbial swords into ploughshares since 2000, when he began re-purposing guns, munitions, and other relics of armed violence like rusty scrap metal into sculptures. Much of his early work with this medium was strictly sculptural art, disturbing renditions of animals and hominids (even one that’s a dead ringer for the junk hording Jawas of 1977’s Star Wars), but more recently he’s used the retired weapons to fashion chairs. It’s a noble endeavor: since TAE’s inception (the acronym stands for “Transformaçaõ de Armas en Enxadas,” or “Transforming Arms into Hoes”), about half a million guns have been converted into works of art, which, besides the brilliant re-invention of implements of destruction as art, brings much-needed attention (and an occasional influx of capital) to the African nation.

As far as the collections’ design merits, one critic has said that “they may prove a tad uncomfortable, given that the backrest is a submachine gun, but the pieces are not about grand comfort.” Indeed, but if you can get past the slightly-less-than accommodating contours and relish the genius of an overtly political artpiece that’s also a grand furnishing, you can appreciate Mabunda’s creations on their own terms. And to add yet another element into this mix, the wide profile and spacious/ornate backrest of the Weapons Chairs recalls the iconic African Tribe Chair, a choice that re-contextualizes the Western World’s long-standing (and unfortunately Colonial) interest in collecting “traditional” African art, as well as the African world’s conception of itself. Whether you love it or hate it (and my reaction is I’d love to sit in it for about fifteen seconds, but could look at it all day long), Mabunda’s piece forces us to think long and hard about the legacy of war, about its surpassing power to irrevocably alter our psyches as well as our aesthetic landscapes.

Leave a Reply