Walk On? A Brief History of the Fall of Armstrong Flooring

Walk into a Whole Foods or a Sprouts and glance down at your feet. What kind of floor are you standing on? Odds are it’s polished concrete. In fact, this material is the specification standard at many of the higher-end grocery stores that began their ascendance in the late 90s and early aughts. Polished concrete can be a great solution for high-use venues that need to convey a design-forward image, but did you know it’s also responsible for the Armstrong Flooring bankruptcy?

*Top Image: Standard Excelon Imperial Texture VCT from Armstrong Flooring

What Went Wrong?

The above is hyperbole, of course, but the rise of concrete is one among many likely factors for the brand’s downfall. Here’s a brief list:

- Tension with Distributors

- Coming late to Commercial LVT

- Never having a carpet line

- Failing to develop a 12 millimeter laminated wood product

- Pivoting to residential and direct-to-consumer sales

- Lack of innovation and business development

- Poor management

- Generally being in the right place at the wrong time

With AHF Flooring’s recent purchase of Armstrong Flooring, we’re now past the bankruptcy stage and on to the “what’s next” moment of this intriguing saga. One imagines that AHF is now in the business of looking forward, but in this article, we’re taking a look back at some of the factors that contributed to the fall of an iconic brand.

Reason 1: Bad Timing, Concrete

Discussions with a couple of industry insiders—Starnet President & CEO Mark Bischoff and Jeff Trattner, Principal Consultant with 360 group and Former VP of Marketing for Roppe Holding Company—suggest that bad timing is a contender for the main cause of Armstrong Flooring’s fall. But is “bad timing” just a euphemism for an absence of forethought? For a lack of creativity? Let’s look at polished concrete as an example. According to Bischoff, Armstrong Flooring formerly had a bit of a monopoly on flooring for the “retail super cycle,” the ascendance of big box entities like Walmart, Kroger, Target, and CVS—whose preferred flooring was vinyl composition tile, an Armstrong specialty. With an entry level price point and decent durability, VCT was “the cheapest thing you could put in that was acceptable.” Then along came the specialty organic grocery phenomena. Says Bischoff, “The marketing story of this was we don’t want to spend on design but rather on better products—that’s how you spin the fact that you can’t afford a floor covering.” Trends can be fickle, however, and soon this cost-cutting measure morphed into a sign of high design. Eventually, the Walmarts of the world began to eschew VCT in favor of polished concrete, leaving Armstrong in the lurch, without a plan or a product to fill this gaping void: from one point of view, bad timing; from another, lack of foresight about burgeoning trends and a failure to hedge bets in the form of innovation and new product development.

Polished Concrete: Still a Mainstay among design-forward brands. Photo by Simon Marsault 🇫🇷 on Unsplash.

Reason #2: Bad Timing, LVT

The rise of LVT as a contributing factor is a bit more nuanced. Trattner sees this product as an especially interesting case since the industry has struggled to define the product precisely, but that hasn’t stopped it selling like gangbusters, back then and now. Bischoff says that during the dawn of high-end commercial LVT (roughly 2002 to 2007), companies like Centiva, Karndean, and Amtico were “blowing it up.” Armstrong Flooring, to the contrary, had been slow to develop a commercial LVT line:

“The distributors were seeing all these wonderful commercial LVT projects and telling Armstrong to get on board… In the meantime, they (distributors) began looking for sources in Europe and Asia and starting to get their capability together around importing products. LVT was the first product that was widely imported by distributors flying over to Europe and Asia to make their own deals, which put a big strain on their relationship with Armstrong.”

Bischoff goes on to note that this had been a company-wide pattern, as Armstrong Flooring was slow to transition to fiberglass-backed technology for sheet vinyl, thus allowing other companies like Mannington, Tarkett, and Gerflor to get ahead of them on commercial heterogeneous. Call it “bad timing.” Call it “missing the boat.” Either way, it begins to seem like a trend.

LVT Flooring from Amtico’s Decor Collection

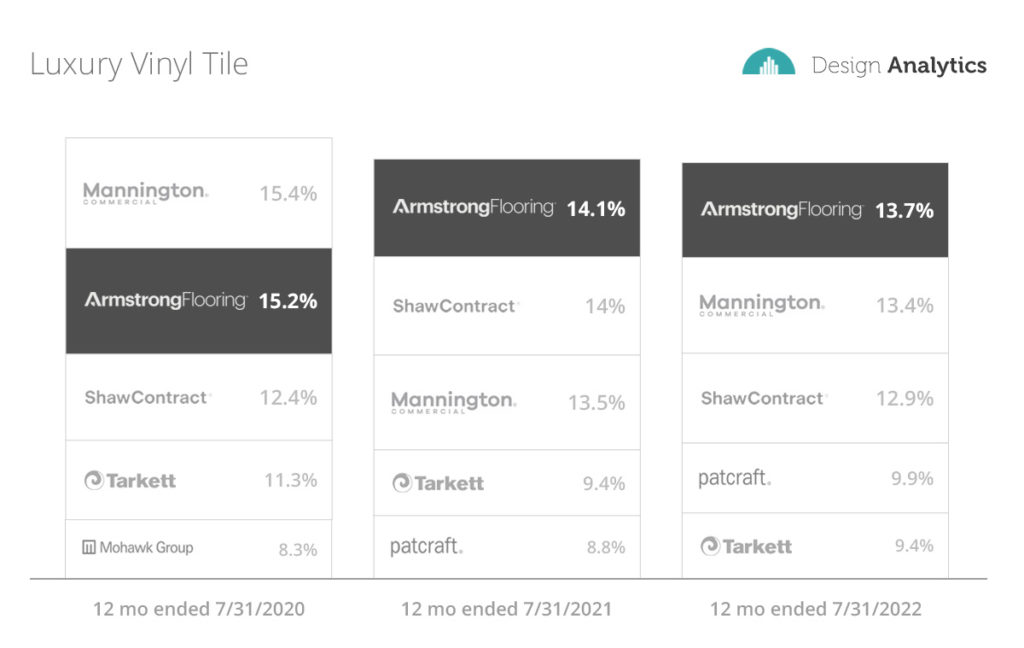

More than concrete or VCT or commercial heterogeneous vinyl, LVT is particularly salient here because it seems to have been at the center of Armstrong Flooring’s business development strategy over the past 12-15 years. Data from Design Analytics suggests that, if they missed the initial LVT boat, they’ve more than caught up. In fact, they’ve been a leader in the LVT category for years.

They’ve also placed substantial focus on innovating their LVT product line. Bischoff points out that the company has their own print film capacity in Pennsylvania, a tremendous competitive advantage since most of the print films come out of Asia. Says Bischoff, “I feel like they were just starting to take advantage of that, and it’s shown in The Good Design and NeoCon awards they received for new LVT designs in 2020 and 2021. Of course, AHF will keep that site and have that capability.”

Armstrong Flooring’s Unbound LVT, winner of a Good Design Award in 2020

Again, this sounds like more “too little, too late.” For the Armstrong Flooring personnel, I imagine these successes have been bittersweet.

Reason #3: Tension with Distributors

The story around LVT transcends the vicissitudes of the product. Back in the early aughts, when companies like Centiva and Amtico were going all-in with LVT, Armstrong may have rightly been accused of leaving its distributors in the lurch. As mentioned earlier, many of these distributors were putting pressure on Armstrong Flooring to focus on (or at least enhance) their commercial LVT line. Their failure to do so sent many of these distributors scrambling for new partnerships. Nor was this a one-off occurrence. Both Trattner and Bischoff mention that these tensions began in the mid 90s, when Armstrong elected to reduce their North American distribution network to 12 members. Says Bischoff,

“They wanted their distributors to be fully committed, not carrying multiple lines, not importing. I imagine they thought that if they gave larger areas to their most professional and financially strong distributors, then they’d get more loyalty and have greater impact in those markets. It worked great for some and not so great for others.”

The above marked the beginning of tensions with distributors, not only because of the requirement to carry only Armstrong products, but also around blurring the lines between commercial and retail distribution. Bischoff says that a particular point of contention involved the appearance of Armstrong products in Lowe’s and Home Depot: “The Armstrong displays started to show up and they wanted their distributors to service them, to check on claims for the big box stores, essentially to do their housekeeping. That’s a hard ask when the distributors are trying to make a living with their own lines” Trattner seems to agree: “Armstrong miscalculated the impact these relationships could have. Most of the distributors survived. But it also forced many distributor sales professionals to find new places to work.”

Reason #4: Divestiture of Wood

In addition to the issues with distributors, the above points to the role wood has played in Armstrong’s difficulties. Bischoff told me that it can be quite difficult to succeed in wood, for a host of reasons, not the least of which are the complications posed by the displays: “The wood business is challenging because of embedded display and sample costs. Armstrong pushed these costs to distribution.”

Of course, it’s not just the displays that make wood challenging. It’s a high-end product with a relatively small customer base (at least for commercial). Plus, manufacturers have always had to deal with a global oversupply of timber products, as well as competition from Canada and China. Again, we see a theme of squandered opportunity. According to Bischoff, Armstrong Flooring missed the boat on laminate, particularly on advancements in 12-millimeter laminate flooring, “which looks as good or better than hardwood.” As the “Kleenex” of hardwood, one imagines Armstrong Flooring would have capitalized on the laminate trend, an honor that instead went to competitor Pergo.

A Pergo floor. The “Kleenex” of laminated wood.

We reported on Armstrong’s surprising divestiture of its wood flooring business back in 2019, a move that ran counter to the strategies of Mohawk, Tarkett, Shaw Contract, and Interface, each of whom were broadening their product mix at the time. Of course, this same move was the genesis of what is now AHF, a company that begins to seem like the embodiment of the future. Why has AHF met with such success? How have they managed to essentially absorb Armstrong Flooring over the years and morph it into a brand new forward-focused company?

Bischoff provides a clue with his take on the way AHF has handled wood. He points out that some of this is a question of timing, as the merchandising protocol that may have hamstrung Armstrong has proved an asset for AHF. This is because the requirements have changed dramatically, particularly during the last couple of years. The cumbersome and space-sucking displays are largely gone. In their place we find, in part, social media. Bischoff remarks that some of the greatest sales of wood now come through Pinterest: “And there are some unique things about wood that are an advantage in the modern consumer experience that you’re not getting with some other products.”

Exceptional detail seen in Hartco’s engineered hardwood flooring.

As an example, in addition to being marketed with traditional displays and panel samples, products by Hartco (a brand of AHF) can now be put into architectural folders or digitally merchandised using visualizers. AHF and their brands have also been on the cutting edge of product innovation. We already mentioned the advances in 12-millimeter laminate. There have also been improvements in the chemistry of the wear layers, resulting in a product that’s much more stable and durable than it was ten years ago. The bottom line, according to Bischoff, is that “AHF is setting the pace with how to do wood at retail… they’re creating a new rule book that everyone has to follow. When you can set the rules, you’re in a much better position.”

A Future without Armstrong

Perhaps this cuts to the heart of Amstrong Flooring’s plight: that the company has long since failed to make the rules. Bischoff points out that many of Starnet’s flooring contractor members have relied on the company as a legacy brand. For some of these, it’s been a family enterprise—multiple generations cultivating relationships with an established company whose calling card is reliability. Bischoff makes a telling analogy: “Armstrong was never outstanding, just very predictable. Many of our members had a high comfort level with them. It was a brand that became like a utility, just a part of how business was done. Very few brands can develop that kind of consistency.”

A bright future as a brand of AHF? Armstrong Flooring’s Duo LVT.

There’s an ennui here that’s likely always present in a major changing of the guard. But I think both Bischoff and Trattner would concur that, in spite of the nostalgia, the sale of Armstrong will ultimately be good for business and good for the industry. While Starnet members wil be affected through a period of transition, particularly with regard to large-scale, high-volume, resilient-heavy projects in healthcare and education, the rise of AHF will mean more innovation and expanding markets. Bischoff suggests as much when he describes his ongoing role as go-between for his members and the manufacturers: “We try to stay above the fray… Connecting the dots around the opportunity rather than dwelling on what went wrong.”

Designer Pages and Design Analytics will continue following this story as AHF takes over operations of the remaining Armstrong Flooring factories. Check back next week for a statistical analysis of how the flooring product mix is likely to be affected. We’ll especially be looking at emerging opportunities for manufacturers. For information on customized analytics solutions, contact Mark Daniel, VP of Analytics, at mark.daniel@analytics.design or 254-488-2350.

Leave a Reply