Magic Parts: the Art and Design of Sabrina Merayo Nuñez

Sabrina Merayo Nuñez is haunted by pianos. Well, maybe “haunted’ isn’t exactly the right word. Perhaps “pursued” is more accurate. As with much of the artist/designer’s work, the piano is a found motif that joins forces with the core idea—making a chest of drawers, or a cabinet, or a mirror, for instance—to emerge as a singular piece of work.

“Accumulations”: Carl Hardt 21472 chest of drawers

“I have a history with pianos,” says Nuñez, “they kind of follow me. There was one in Italy and three here (in NYC)… one that I found in front of my house, one in my studio. The Carl Hardt piece is now in Spain.” Looking at her work, one gets a sense that Nuñez has a kind of magnetic effect on objects, and they on her, as the collection of disparate parts and re-contextualized wholes that cohere into a finished piece constitute the palette for her work. All of that, as well as the tools of the woodworker’s trade: chisel and saw and router and, to create the outlines for the oft-integrated smaller objects, a very sharp Exacto knife.

Nuñez’ workbench at her “Cabinet Lab” one-person show. That’s a lot of chisels!

To this list of what constitutes her palette, I should also add a rarefied aesthetic, one that blends the influences of pre-industrial-revolution furniture (especially the mechanical furniture of France); a profound appreciation for the nature of wood; and the films of Terry Gilliam (Brazil), Tim Burton (Edward Scissorhands), and Jean-Pierre Jeunet (City of Lost Children).

Jeliza Rose’s Cabinet. Named after the character from Gilliam’s Tideland: “The cabinet is a typology that arose for the purpose of storing and exhibiting collections in the 16th century.”

Nuñez is schooled in the visual arts. She studied at the University of Buenos Aires and then went on to obtain a degree in Fine Arts at Prilidiano Pueyrredón School in Argentina. This background provides another piece in the puzzle that is her aesthetic and overall artistic vision, yet it remains an incomplete picture until we know more about her hands-on experience with wood.

The Femmena cabinet from the Accumulations series. Made of “Aluminum, watches, 20’s Singer sewing machine parts, chains, small violin, pearls, braided hair, watch glass, washers, 20’s Underwood typewriter parts, leather scraps, halberds, bijouterie, screws, plush, Etore Berlioz orchestration book (c. 1860), sand, Argentinian bills (1970-1983)”

Nuñez realized fairly early in her career that she would not receive education in pre-industrial-revolution furniture if she continued down a conventional path, “so I decided to build my own education. I studied the history of furniture, Valuation of Artworks and Decorative Arts at Universidad del Museo Social Argentino and then I was a trainee at wood-workers ateliers.”

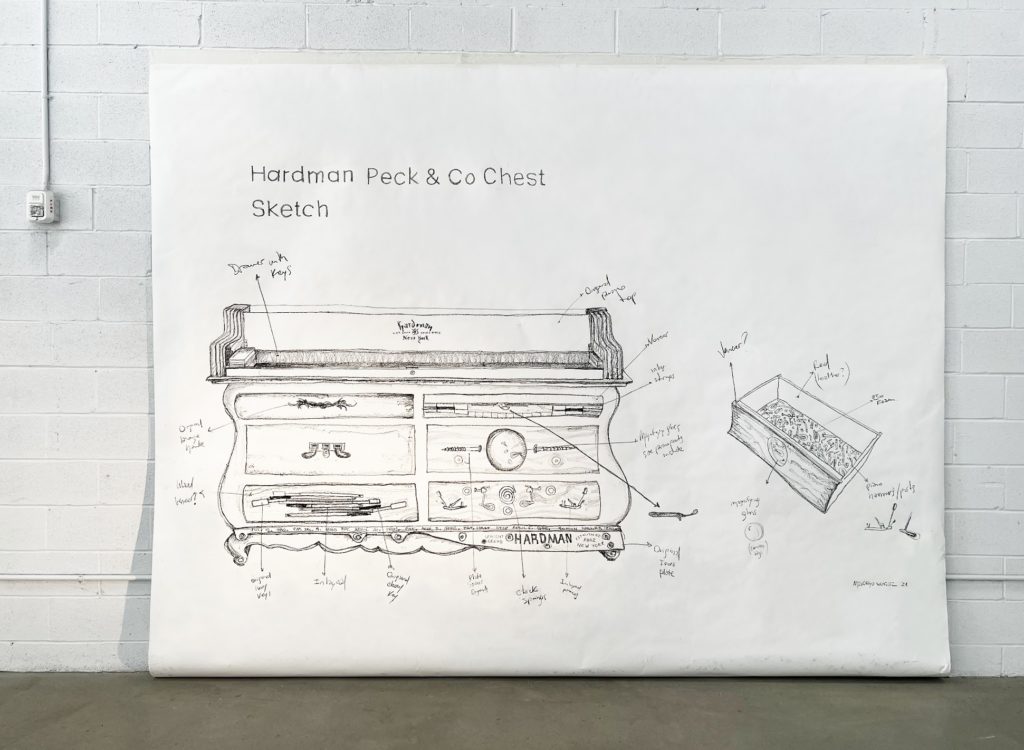

A sketch for her latest project: a chest of drawers incorporating parts from an original Hardman Peck & Co piano

Her time in these ateliers was in keeping with the venerated apprenticeship model, in which the novice devotes time to what may seem like menial tasks but which gradually coalesce into valuable skills. The emphasis was on watching, intuiting, absorbing, and learning—to evoke more cinema, sort of in the spirit of The Karate Kid: “These kinds of workshops still work somewhat like medieval workshops, in the sense that the craft is learned step by step and as the confidence in the disciple grows, the transmission of knowledge is strengthened. There is not only one way of making. Each master has his own way, and I learned and took from each one what had more to do with me.”

Doble Milano from the “Joints” collection, a study of antique furniture construction

The next phase in Nuñez’ evolution involved a deep investigation into the nature of wood. And I mean that in the most literal sense of the word, as in DNA-deep. She describes experiencing a revelation of sorts when, after she had been working for a while in Argentina, she visited a sawmill: “I realized that the ‘thing’ with which I had been working for so long was actually a tree.”

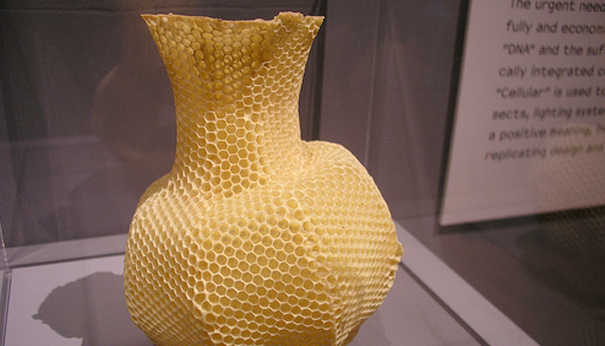

Spinning a tree down into its elemental parts: “Having the key of life (DNA) puts us in the situation to stop thinking about nature as an ‘other’ and understand that as human beings we are unified by the same laws of life.“

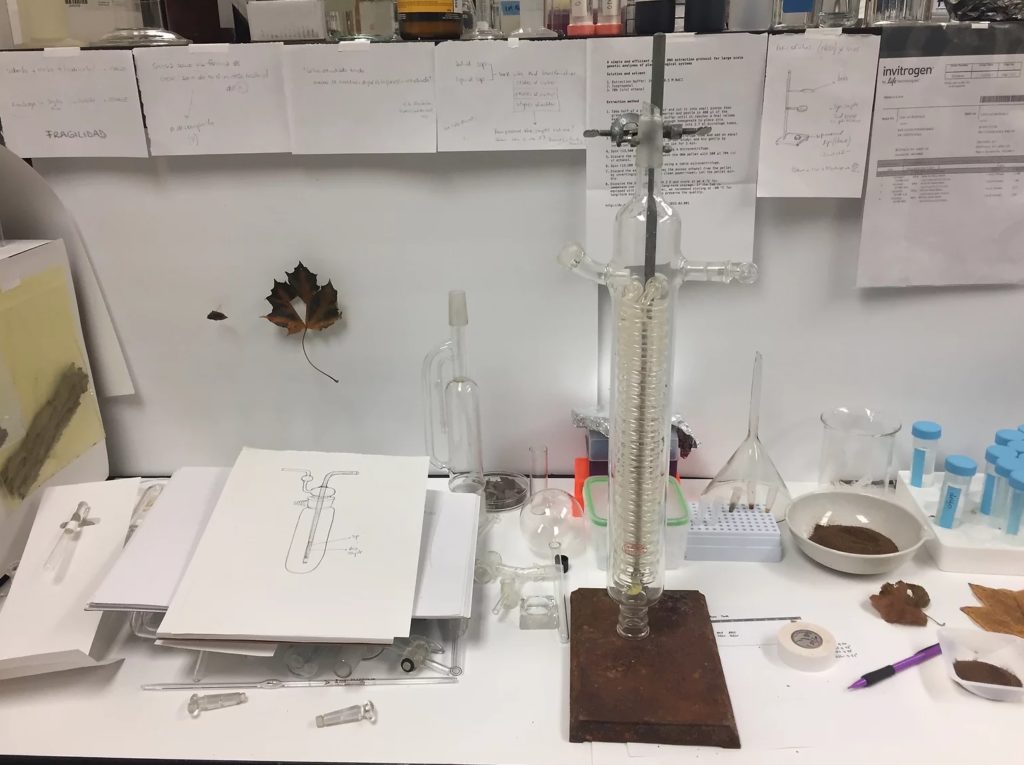

Her re-ignited appreciation for the material left her yearning to explore it to the very last detail. Hence, she pursued a residency at the Coalesce Center for Biological Art, an experience that continues to shape her ideas about what wood is—how in many ways we share the same basic blueprint for life and that the distinction between “I” and the “other” (even when it’s a tree), is somewhat contrived. Working with scientists also broadened her perspective by further contributing to the dissolution of these artificial distinctions, between “science” and “art” for instance: “Sometimes the combination creates a synergy. You may have some questions or ideas about your subject that the scientist doesn’t have, and in the middle you find a lot of material to work with.”

Orpheus cabinet from “Cabinet Lab,” her first solo show in the U.S. Space provided by ChaShaMa.

Investigating wood at the cellular level has translated into more expression of organic shapes, especially in her current exhibition, “Cabinet Lab” a solo show at ChaShaMa in Midtown, running through February 27. Cabinet Lab features several of her latest pieces, including “Orpheus” (above), an homage to Jean Cocteau’s film (yet again, more cinema), as well as “Hammers Mirror,” “Resolute Bead Mirror,” and “Sprouted Chair.”

Sprouted Chair. Yes, it’s alive.

Each in their own way, the pieces in Cabinet Lab are informed by Nuñez’ interest in organic forms. As with the Accumulations pieces, they’re still created in her signature eclectic and piecemeal way, and the stuff of their making has the same kind of treasure chest appeal, yet the disparate parts don’t seem quite as neatly stitched together. This manifests not only in curvier, more asynchronous shapes, but also in a subtext of organic propagation—a more recognizable facsimile of the messy stuff of life.

Resolute Bead Mirror. Note the peekaboo hole that provides a glimpse of the “reality” behind the mirror: “I like to think of mirrors as windows to other dimensions. Whenever we look at a mirror we are looking at the present in real time. And that is quite similar to eternity, to an infinite present.”

The organic element of the Sprouted chair is overt, as the wood very clearly has developed a mind of its own. With Orpheus, it’s perhaps a bit more elusive, but certainly the intersection of human and material is a prominent motif, especially when you open it and encounter the carmine-colored collection of piano parts, which at a glance might be mistaken for internal organs swimming in a murky plasma.

Orpheus. Detail of interior.

Cabinet Lab is also organic in the sense that it’s spontaneous. The show is literally an ongoing work in progress, as Nuñez continues the project of making her Hardman Peck & Co. chest each day. She relishes this opportunity for an audience to experience her process, as it’s one more way to tell a story: “People can see how i think about the objects. I love the craft process and the relationship between the maker, and the tools, and the different gestures, all of the marks that you leave on the piece.”

Making her mark. Nuñez at work on her Hardman Peck & Co. chest of drawers at the show.

As is probably apparent by now, it’s difficult to contextualize Nuñez’ work. When the inevitable questions arose (is it “art” or “design”? Is everything for sale? Have you thought about making more “commercial” furniture?), she deftly dismantled the premises of the questions, especially the one about “art” vs. “design”: “this is something that I ask myself quite often, as if there was this clear boundary… the whole history of art and design show us that nothing is so simple. They’re interwoven. I like to find the places where both are allowed.”

Is this a writing desk? A vanity table? A Camera? Isn’t it so much nicer not to know? The Beseler 23C II desk.

They’re both allowed in her imagination and in mine. Certainly in the mind of anyone who attends her show. And in yours too, I hope. Because we need more furniture (and art, for that matter) that invites dialogue, that tells a story, that interweaves the history of objects with the present moment of making something and also choosing to acquire something. After all, “these are the tools we use to create our spaces, the objects that are with us every day. Sometimes we don’t pay attention but we should… because they are very important.”

Come see the Cabinet Lab show at ChaShaMa, 1155 Avenue of the Americas in Midtown, from now until February 27, open every day except Sunday, 12-5:30.

Leave a Reply