A 60s-Era Milan Apartment by Ettore Sottsass is Exactingly Reconstructed at the Triennale Milano

We’ve all been inside a museum that portends to a period reconstruction: an ancient bedroom in Pompei, the crumbling stone eroding the vibrant frescoes on the walls with geological precision; a gilded Louis XIV credenza adjacent to a massive four-post bed, the walls beyond hung with tapestry thick as buffalo hide; the exacting joinery of the Shakers, exemplified in cupboards or desks or ingeniously inventive kitchen implements.

A Tantalizing View of a Corridor from Casa Lana

These kinds of recapitulations—or partial re-assemblings, or hybrid depictions made from both authentic and faithfully re-imagined elements—are hardly new. Most museums have them, in one form or another. But the Sala Sottsass at the Triennale Milano is a rare instance of a comprehensive and completely authentic reconstruction.

An original Sottsass drawing of the Casa Lana interior

Up the Stairs at the Triennale Milano on the way to Sala Sottsass

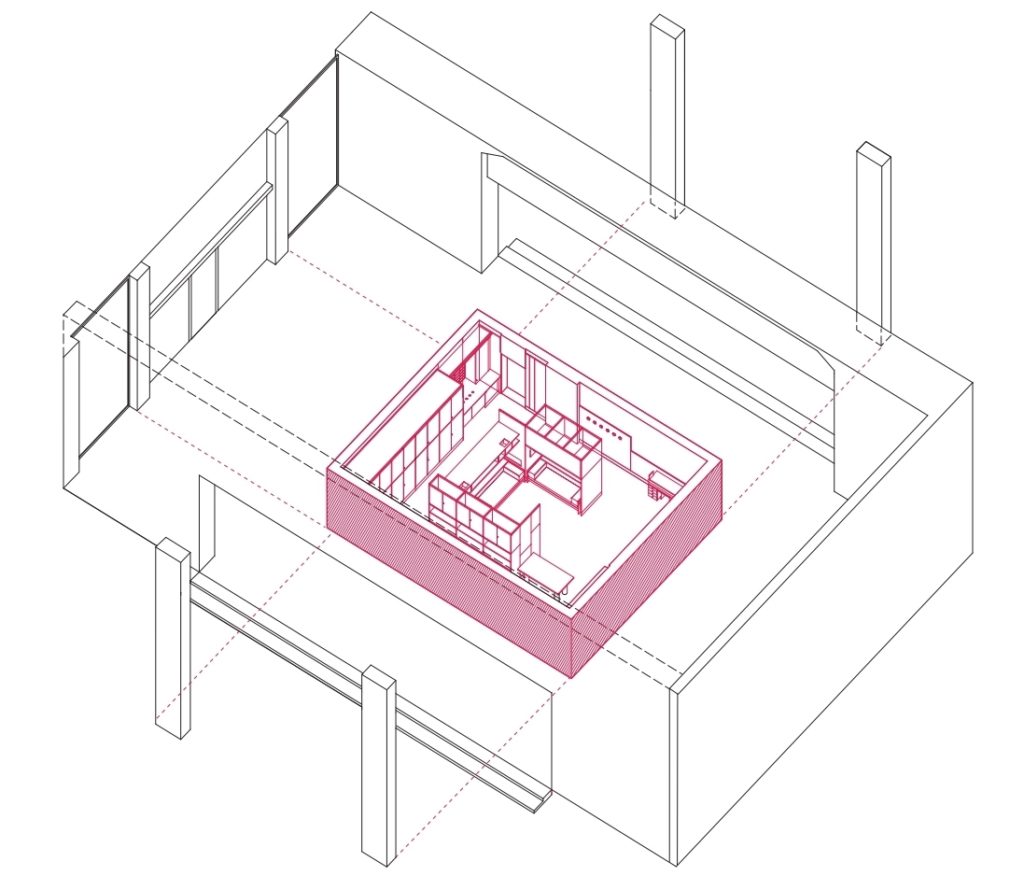

In fact, “relocation” may be a better word. Sala Sottsass, which opened on December 3, contains the entire contents of Casa Lana, effectively moving what Sottsass himself characterized as a “room within a room” from the original apartment in the center of Milan to what one critic has described as “a room in a room inside a flaming red box in the hall of a museum.”

The Struttura E Colore exhibit flanks the walls of Casa Lana

The space, originally designed by Sottsass for his friend, the printer and lithographer Giovanni Lana, is an homage to the rectilinear and the compartmentalized—to the mashrabiya screen and its gentle filtration of light, to the eclectic interaction between the hushed tones of natural wood and the screaming-at-the-top-of-your-lungs exclamations of fire-red fabric. Yes, there’s lots of juxtaposition in this space, as it very much captures the Avant Garde of the moment: “A real time machine,” according to Stefano Boeri, President of Triennale Milano, “created by one of the international geniuses of the twentieth century.”

Peeking around the walls into the heart of Casa Lana. Photo: @Gianluca di loia

How was this veritable prestidigitation, this transposition of a formidable collection of mid-century design archetypes, achieved? According to the Triennale’s fashion and crafts curator Marco Sammicheli, so very much depended on the integrity of the original space: “The opportunity to secure Casa Lana came to us thanks to the Lana heirs and to the generosity of the Ettore Sottsass Archive and due to the extraordinary integrity of the apartment. It is as if Casa Lana was frozen in time, precisely as the architect designed it.”

Photo:@Gianluca di loia

The excellent images from the Triennale certainly tell this tale: Casa Lana was and continues to be a profusion of rooms within rooms, spaces within spaces, nooks upon crannies upon cozy niches and corridors. And though I’m not a particular fan of LEDs, in this instance they’re not a bad facsimile for the Italian light, insinuating itself through the mashrabiya screens, tickling the profusion of wood panels, spilling onto the continual canvas of carpet, the effrontery of its shocking red somewhat quelled by the scattered specks of illumination.

Photo:@Gianluca di loia

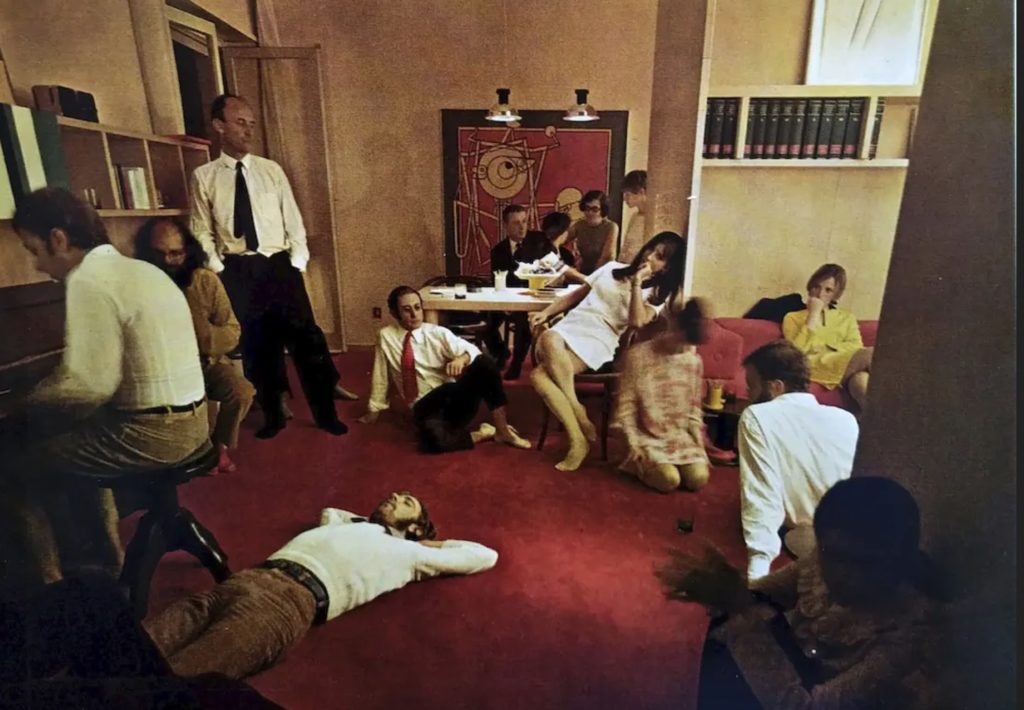

It feels like a cozy space and an encompassing one. Like a room that can be extraordinarily private and jubilantly social. In fact, it strikes me that the thematic underpinning could have served us well during lockdown days. The central premise of a flexible nook that both welcomes and cordons off—as Sottsass described it, “a little piazza… where one can move and meet”—echoes the form and function of much contemporary ancillary furniture, the privacy nooks, high-back sofas, and assorted pods that fulfill the dual imperative of a private respite and collaborative zone.

Original Image of the living room at Casa Lana, circa 1967

Photo: @Gianluca di loia

Yet Casa Lana was made for living, not working, nor for live/work, in the current nomenclature that recognizes how most of our spaces are blurring the distinction. To the contrary, this late 60s gem seems to celebrate this particular historical moment of domesticity. The space not only feels like a room within a room, but a room within its very own universe. Except for the slants of light spilling through, Casa Lana offers no indication of the life outside its walls, of the bustling motley that happens mere feet away from any apartment in most any city.

Built-Ins contributing to the feel of a self-contained space. Photo: @Gianluca di loia

Is this a good thing? Do we want our spaces to feel so self-contained? So separate from the universal threads that connect all things? I think yes and no and it depends: on the place, on the mood, on the particular emotional vicissitudes of the inhabitants and their visitors.

photo: @Gianluca di loia

Better said, sometimes a comprehensive respite is entirely warranted and completely desired. I, for one, relish the wholesale immersion into one of Sottsass’ “Artificial Environments,” spaces not for biding time, but for existing, for being in the present, as much as such a thing can be done: “There is someone who designs the place to wait and someone who designs a glass to let people know what is wine. I always thought that maybe I could try to design places where I could find some strength to wait or maybe I could also draw a very red box that should never be opened so as not to let the enigma out.”

Leave a Reply