Being Erwan Bouroullec: An Exclusive Interview

As a product reviewer, one of my favorite moments is finding a product that’s easy to compare to something else. Why? Because this not only kickstarts the writing process but also creates an accessible point of entry for the reader. In fact, comparing is a fundamental requirement for any piece of writing. Comparing is the basis of metaphor, which is the only effective way to get someone to understand something, short of them being directly in its presence. And I’m not only discussing the simple formulation of “this is like that” but also “this is an example of that.”

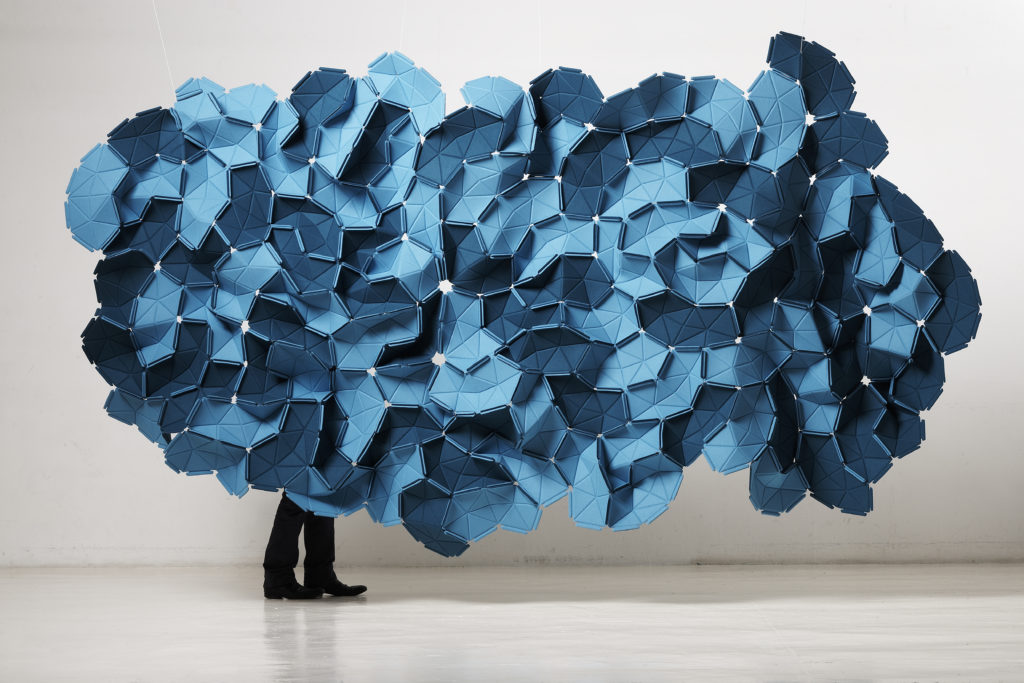

Clouds for Kvadrat: a form both familiar and foreign

Image credit: ©Tahon & Bouroullec

Erwan Bourollec’s knack for comparing makes him an incredibly engaging speaker. During our interview, he half-deprecatingly referred to himself as a “pipette,” which translates in English as something like “motormouth.” But that doesn’t do justice to his style or his enthusiasm. And further, the actual meaning in French lexicon and culture is somewhat kinder. Yes, he can go on, but his observations are pithy, engaging, thoughtful, and fun. What’s more, you can see him thinking through a concept as he speaks—trying out certain ideas, reaching and grasping for the right terminology, rejecting it, grasping at it again, evolving and advancing his point, and, of course (he is French after all), taking a well-timed pause for a deep drag on a jauntily held cigarette—hand-rolled, I would venture, were I a betting man.

Lit Clos (“Box Bed”) for Galerie Kreo

Image credit: ©Morgane Le Gall

We recorded our interview; I then transcribed it and have since spent several hours parsing its contents, tricking together the disparate threads, attempting to come up with an over-riding theme. Of course, there is none, nor should there be, this being a casual conversation and pretty much un-prepped, but on close inspection some of those threads do cohere, do twine their wisps around each other and eventually become a single strand of textile.

North tiles for Kvadrat

Image credit: ©Paul Tahon and R & E Bouroullec

We discussed many topics, not limited to working with Emeco on the new Truss Collection; American manifest destiny vs. the communal ethos of Europe; the true meaning of “self-sufficiency”; the elemental language of manufacturing; the intransigence of plastic; cave drawings; children jumping on a triangle; shapes of the countryside vs. shapes of the city; the difference between practice and thought; the Stone Roses; the Model-T; Burgundy wine; and coffee and donuts on a steel bench.

Truss Table for Emeco: “We had no way of making a proper photo shoot… they were real workers under pressure of finishing, so they were just shot around the table having this great time.”

Since 3rings is principally a product-focused publication, I somewhat regrettably must truncate this list, constrain it to ways that let me comment on the products the Brothers Bouroullec have made. If pressed, I’d say the central theme of our conversation was about simplicity in design. And here I’m already straying some, because, though Erwan uses this term liberally, he hedges every time, averring that this isn’t quite the right word. Other words? Archaic, elemental, atavistic, intuitive. It has to do with apprehending something and recognizing it, seeing something and immediately knowing beyond thought what it is and how it works and what it’s meant to do. And beyond that, even, how it was made.

Truss

Perhaps the best way to get at this concept is to let Erwan’s words do much of the work, to quote him in his unadulterated and immensely expressive English (and remember, this is his second or possibly even third language) and let the products speak for themselves via exemplification and my essential process of comparing.

Aim pendants for Flos

Image credit: ©Philippe Jarrigeon

Quote 1: “I have a dream about the American factory without having ever been there. You know, there’s something in design which is very important, which is the past. Most everything you use for any furniture, tools, they’re connected to a kind of an ancient pattern which your mind recognizes very quickly. In the case of Truss, it’s basically adding a triangle to a frame.”

Bouroullec comes back to this again and again—the idea of an elemental recognition and understanding. Truss is a perfect example. As he explained, it’s basically just a triangle attached to two planks of wood. He also pointed out that everybody knows what this shape is and what it can do: “You remove the triangle, it’s wobbly and soft. Just by putting the triangle in it’s incredibly strong… if I would tell you go and jump on it, you wouldn’t ask a minute. You would just go jump.”

Copenhagen Collection for Hay: the triangle in the Bouroullec’s design lexicon circa 2012

Image credit: ©Studio Bouroullec

Quote 2: “Sometimes when you’re in the countryside and there’s farming equipment and things like this, most of the time it requires getting straight to the point. You know, like a fence is a fence for animals. There’s a beauty, but most of the time it’s like very very very limited. And by the way, when I was doing Truss I was still thinking of doing a fence.”

He also said of the Truss table that it’s way too long. The excessive length of the pieces in this product family is intentional, not only because the unused terrain begs for companionship (“there is also one other possibility that some of the people start to share the table with you”), but also because their modularity creates a scenic continuity—the benches strung together in repetition of the triangular pattern, like a simple truss-style fence wending its way across a grassy field.

Fence on Dallas Divide, Colorado

As Erwan spoke about the triangle, I’d begun to think about right angles, about geometry and design and the simplicity of working with rigid materials. And whether his work was generally characterized by this. Presenting him with this idea, he showed me the Osso Chair.

Osso chair for Mattiazzi

Credit: @Studio Bouroullec

Quote 3: “I was trying to do comfortable chair in wood, and, you know, one of the issues with wood is the curve, exactly as you said before. So wood, you know, it come in a plank. So either you curve the plank or take a big volume and you carve the curve out. It’s not 100% easy… So, yes, I’m incredibly careful in the way I’m making change to material. But it still doesn’t mean that curve or softness will disappear.”

Osso Collection

credit: @studioBouroullec

He’d shown me how wood could be made to curve without brutalizing it (he’d also talked about the tragedy of polyurethane surface treatments: “There’s no more breathing, no more air going in and it’s costing a lot of energy to fight against this nature.”), next, he moved on to other ways in which products could depart from purely geometric configurations—and which materials could aid this.

Alcove Highback sofa for Vitra

Image credit: ©Paul Tahon et Ronan Bouroullec

Quote 4: “There’s something I love a lot which is textile. I’m doing a lot with textile and textile can be different. Like this sofa…”

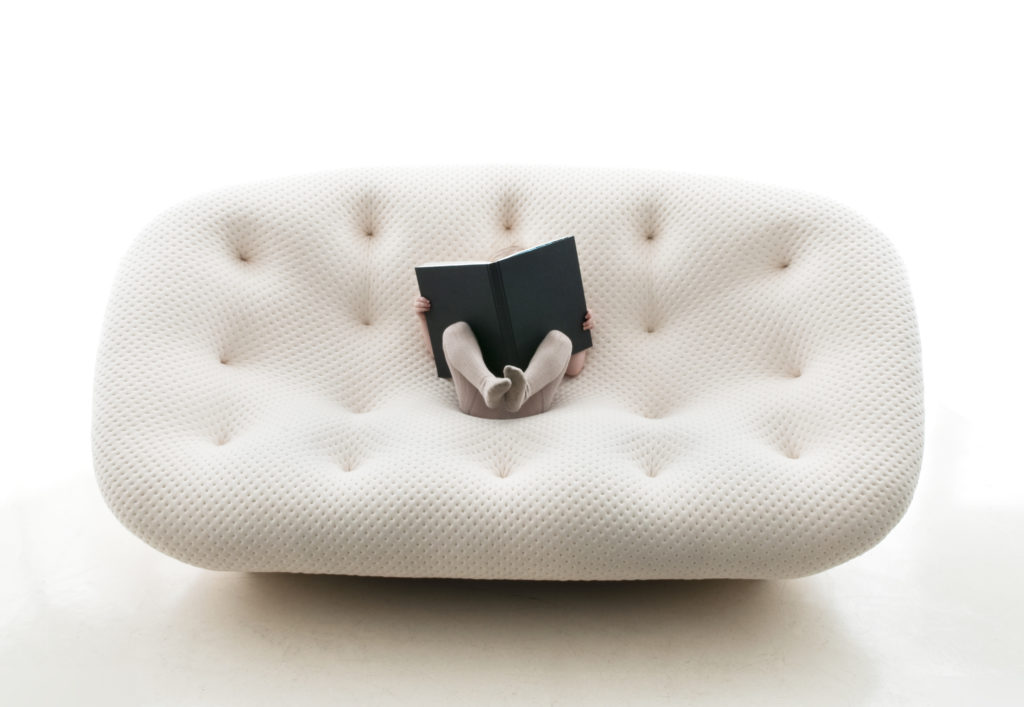

Ploum for Ligne Roset

Image credit: @Ligne Roset

Bouroullec comes back again and again to the immediacy of the experience, to the knowing and the participating in. As he says, Ploum is just a gigantic, stretchable textile. You see it and you don’t have to think about it. You know what it is and you want to experience it. Jump onto it and inside of it. Give yourself over to it: “It’s just a big bathtub of foam. It’s fucking comfortable. It’s just incredibly comfortable.”

Ploum

Image credit: @studioBouroullec

Quote 5: “I know that design is not here to change the world but sometime we can still provoke some very deep sensations to the people. But, again, these sensations are very subconscious. They don’t think about the sofa. They practice it. Which is very unlike art piece. Art piece, you think about it, but you don’t practice it. It’s not the same rules that design has compared to art.”

Basket sofa for Cappellini

Image credit: @Cappellini

Had he gone on, he might have convinced me (a born aesthete) that design is in fact superior to art, though this wasn’t necessarily his intention. In any case, Ploum nicely illustrates this idea of an immediate, immersive experience—how it can preclude thought and how it often defines the nature (in many ways) of good design.

Ploum sofa

Image credit: @studioBouroullec

Given Erwan’s praise of “basic” manufacturing, of elemental shapes and the way they convey information about how something works and what it’s meant to do, one might be tempted to assume that he eschews plastic.

Fleurs for Iitala

Image credit: @Studio Bouroullec

Quote 6: “You really need to be an expert to understand the logic of the shape. Plastic has very strange rules that are not common… if I start to explain why this shape is like this, it can take quite a while, and I’m not sure you would understand.”

Rope Chair for Artek

Image credit: @Studio Bouroullec

He also says that plastic, “doesn’t like to be flat.” How, then, do we reconcile this attitude (if not derisive than certainly a bit reluctant) with his considerable output in plastic, like Algues, The Vegetal Chair, and the intricate and enchanting Nuages?

Nuage storage modules for Galerie Kreo

Image credit: ©Ronan et Erwan Bouroullec

Because if plastic is somehow foreign—If it conforms in odd ways, if its mechanical properties are too arcane to apprehend, let alone explain—then how can we call it “recognizable,” how does it meet the qualification of being “simple”?

Algues for Vitra

Image credit: ©Tahon & Bouroullec

The answer may be found in my opening comments about likening something to something else, as each of these pieces has the advantage of comparison. That is, they all look like something that is not furniture, something we all understand, something everyone has experience with: Nuages is like a honeycomb; Algues resembles tentacular strands of deep-sea algae; and Vegetal not only appears a facsimile of spiraling branches, but actually duplicates this growth via the wonders of mathematical extrapolation.

Vegetal Chair for Vitra

Image credit: ©Paul Tahon and R & E Bouroullec

Quote 7: “I’m not a chef, but I like the very direct expression you can have inside a flavor, so, yeah, probably this kind of elemental thing I’m describing is kind of linked to a very elemental sensation of the world.”

Filo Chair for Mattiazzi: Erwan says he’s not a chef, but this chair looks like extruded pasta

Image credit: ©Gerhardt Kellermann

His comments about food help put the ideas in perspective. I think back to the distinction he draws between the practice of design and the practice of art, a difference he exemplifies by evoking narrative: “Art and movie are a very different practice because you enter into a story or conceptual thing, so you think about it in a certain way… you enjoy it through the reflection.”

Ensemble exhibition for Mutina

Image credit: @Mutina

Part of the difference, then, involves time, because the average experience of design is immediate; it happens and then it’s gone; it doesn’t really tell a story. Design, in Erwan’s formulation, is about achieving comfort, yes, but also about this timeless moment, about invoking a form or idea that you can experience in a tactile way, that transports you immediately, “You see something, you practice it, and then you totally forget about your body… you just enjoy it… you feel safe.”

Ploum

Image credit: @studioBouroullec

In talking with him even briefly, one sees that Bouroullec is passionate not only about design, but also about music, food, reading, culture, collaboration—the alchemy that it takes to create beautiful products. He also seems to be quintessentially European. I say this because we kept coming back to this distinction between space in America and Europe and how it influences political and cultural thought.

Erwan and Ronan Bouroullec in their Paris studio

Image credit: ©Alexandre Tabaste

Toward the end of our time, the conversation turned towards COVID and the proverbial bright side. Bourollec observed that he is seeing a move away from complexity, which I understood—perhaps in my pre-conceived notions of what it means to simplify one’s life—as a kind of characteristic American take on self-sufficiency, of building your own home, hunting or growing your own food… basically a striking-out-and-building-your-own-cabin-in-the-woods kind of simplicity.

Bouroullec Studio, circa 2007

Image credit: ©Ronan et Erwan Bouroullec

Bouroullec’s reaction to my mis-read seems a fitting way to conclude:

Quote 8: “Me, I’m an urban man, so to me being self-sufficient is earning money, paying tax, making sure so people in my community can have a life… This is being self-sufficient in a way. There’s a collectivity that is taking care of each other. So I’m not at all preaching for self-sufficiency when it’s become about isolation. That is not my way. Being more aware of what you are doing as a citizen is the goal to me.”

Leave a Reply